Actions Follow Incentives, Not Policies

Reflections from an OT Cybersecurity Practitioner

In Part 1 and Part 2 of this series, I reflected on how OT cybersecurity maturity is shaped more by governance, visibility, and decision-making than by technology. A third pattern that emerges repeatedly across OT environments is the role of incentives, particularly the gap between what organisations ask for in policy and what they reward in practice.

Policies express organisational intent.

Incentives drive organisational behaviour.

When those diverge, incentives win every time.

Operational teams are incentivised to maintain uptime, avoid disruption, and ensure safe, continuous operations. Executive teams are incentivised to deliver performance, meet regulatory obligations, and avoid reputational impact. In contrast, cybersecurity is often positioned as a constraint on these priorities rather than a contributor to them. The outcome is not resistance, but rational trade-off.

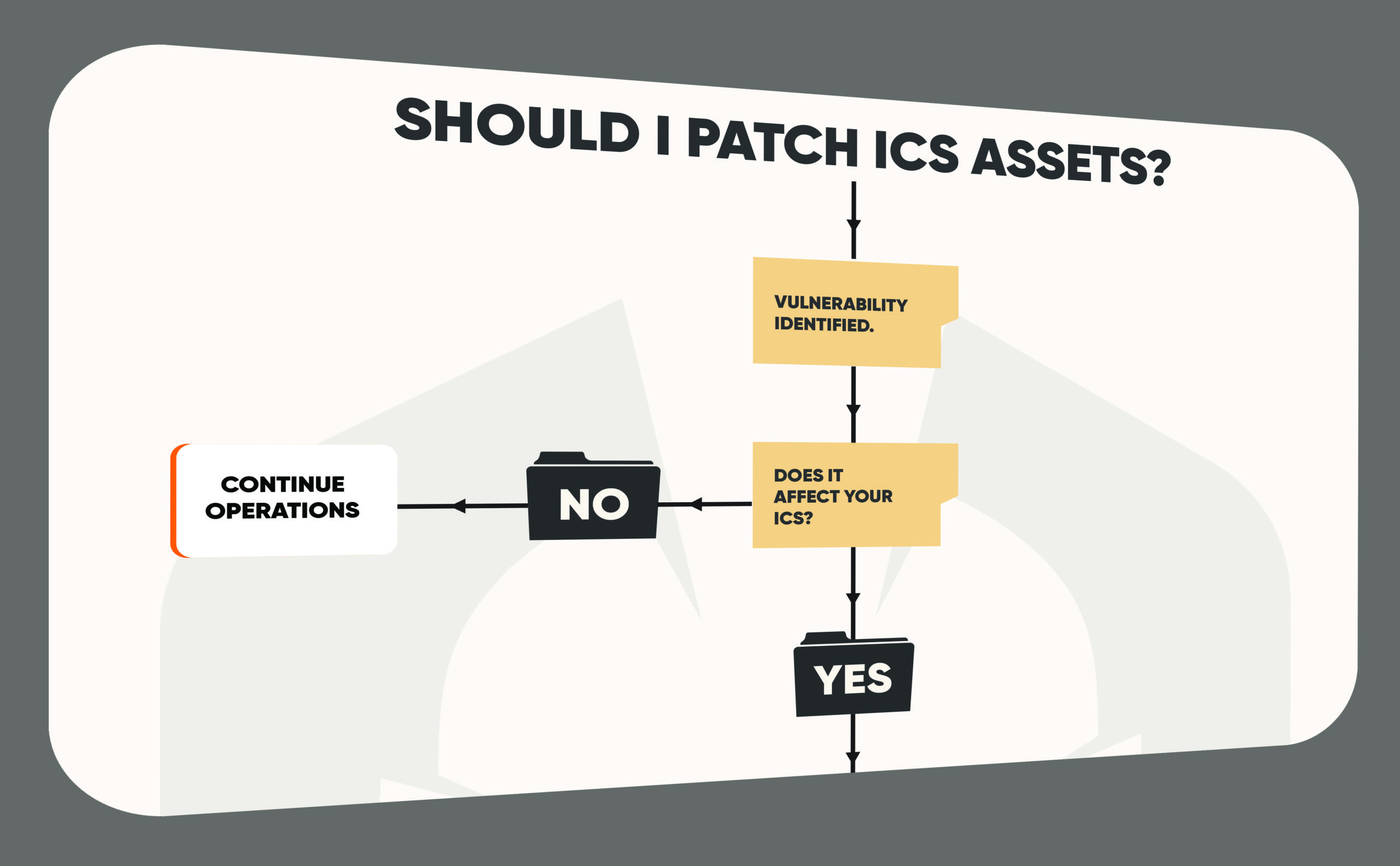

Incentives shape choices quietly. No one has to say “don’t patch”, but when uptime is rewarded and patching is not, the message is already clear.

When incentives reward stability over transparency, deferral becomes the safest choice. When incentives reward continuity over change, exceptions accumulate. When incentives reward looking in control rather than being in control, risk becomes something that is managed on paper instead of reduced in reality.

None of this implies bad intent. It reflects the reality that people optimise for what they are measured against and judged on. It’s difficult to ask people to act against the incentive structure that governs their success.

For practitioners, this incentive gap becomes particularly visible when recommendations reach the point of decision. Technically viable actions can stall, not because they lack understanding or approval, but because they lack ownership under an incentive model that makes action costly and inaction benign. “If we ignore it, nothing happens” is a powerful, if unspoken, incentive. In OT environments, this dynamic is amplified.

Safety cases, certification requirements, and vendor dependencies create structural friction. Maintenance windows are negotiated, not assumed. “Soon” can mean a regulatory cycle rather than a sprint, and “temporary exception” can quietly become the status quo. Within that context, risk acceptance can become a mechanism for preserving operational incentives without appearing to disregard cyber risk.

More mature organisations recognise that incentives are not simply HR constructs. They are the practical expression of what the organisation values. They align incentives with the behaviours required to reduce cyber risk, and they treat operational constraints as design inputs rather than excuses.

In these environments, cybersecurity becomes a contributor to reliability rather than an external pressure on operations. Remediation becomes less adversarial, risk conversations become more honest, and accountability becomes clearer. Progress accelerates not because effort increases, but because the organisation is no longer asking individuals to work against the systems that shape their decisions.

At OTIFYD, we routinely see the difference when incentives are aligned with outcomes. Visibility improves, remediation gains momentum, and decisions become more realistic. Small adjustments in how success is defined can unlock progress that stalled for years.

OT cybersecurity does not struggle due to a lack of policy, guidance, or standards. It struggles when policy and incentives diverge. Closing that gap is not a technical task. It is an organisational one.

By Serkan Yusuf (January 2026)